Contact us if you have any queries.

Due to their lack of maturity, experience and hazard awareness, young people may perceive risk differently to more practiced employees. There is also a raft of various regulatory instruments in place to limit young people’s exposure to specific physical, chemical and biological risks as they are at increased danger of harm from these. This article looks at the factors employers need to consider to instil safe behaviour among a young workforce.

Due to their lack of maturity, experience and hazard awareness, young people may perceive risk differently to more practiced employees. There is also a raft of various regulatory instruments in place to limit young people’s exposure to specific physical, chemical and biological risks as they are at increased danger of harm from these. This article looks at the factors employers need to consider to instil safe behaviour among a young workforce.

A young person is defined in legislation as any person under the age of 18 who is not a child, ie someone who has not yet reached the minimum school leaving age of 16.

In terms of the health and safety of young workers, there are two primary considerations for employers when it comes to reviewing their risk assessment.

Before a young person starts work, the employer’s risk assessment must take into account a young person’s lack of experience, training and awareness of risk as well as their immaturity.

Risk assessments need not be overly burdensome or bureaucratic, eg in an office or shop environment, the organisation’s generic risk assessment is likely to be sufficient and the control measures in place are likely to be familiar to young persons. However, in higher-risk environments, consideration needs to be given to how young people may be influenced or pressured into unsafe work practices by older colleagues or peers, how they may be curious and act unpredictably despite any instructions or training they may have been given to the contrary or how they may also deliberately violate rules and procedures, eg in feeling pressure to get a task done, they take shortcuts.

Appropriate control measures in these cases include:

In higher-risk environments, such as in assembly, industrial or construction sites, along with considerations of a young person’s lack of maturity and experience, specific risk factors also need to be reviewed and additional arrangements are likely to be required.

Young persons have a physical immaturity and an increased risk of musculoskeletal damage as bones and supporting muscles are not fully developed until a person is approximately age 25. This means high levels or prolonged periods of exposure to vibration — particularly low-frequency whole-body vibration — should be avoided.

Young people may be less skilled in handling and moving techniques or in pacing their work tasks to match their capacity. Other jobs that require repetitive or forceful movements, particularly when in association with awkward posture and/or insufficient recovery time, should be given careful consideration. Manual handling of tools and equipment to assist with difficult handling tasks, introduction of task rotation and provision of sufficient rest breaks may be necessary.

Young people should not be permitted to use high-risk lifting machinery such as cranes, lifting accessories and construction site hoists, unless they have had the appropriate level of competence and training. As part of their training, they may use such equipment, providing they are adequately supervised. Adequate supervision should also be provided after training if a young person is considered not sufficiently mature.

The duty to carry out periodic, thorough examinations or inspections of lifting equipment or the planning and supervision of lifting operations, should not be placed on a young person but discharged by a competent adult employee.

Young persons should also not be permitted to use high-risk work equipment (such as abrasive wheels, circular saws, power presses and band saws), apart from during training which is adequately supervised.

The dose limit of ionising radiation should be set at a lower level than that for other employees — doses must not exceed 6mSv in any calendar year.

Many chemical agents can have adverse health effects on young people, although they are typically not considered to be at any greater risk than other employees and control measures currently in place to prevent employee exposure are likely to be sufficient for young people also. Safety data sheets will provide full details on specific agents.

However, a lack of perception of danger may prevent young people from recognising “invisible” or long-term health effects that may take many years to develop. For this reason, specific prohibitions are in place around agents such as lead and asbestos.

Young persons may not be involved with specific lead smelting and refining processes or in lead battery manufacturing process. Exposure to lead alkyls is particularly hazardous and its absorption into the body can produce a rapid toxic effect. Employers should ensure that adequate and proper safeguards are in force to protect the health of any young person employed on storage-tank cleaning work, which could potentially expose them to lead alkyls.

Younger people, if routinely exposed to asbestos fibres over time, are at greater risk of developing asbestos-related disease than older workers. This is due to the time it takes for the body to develop symptoms after exposure to asbestos. Similar concerns exist for exposure to silica dust in the construction industry leading to silicosis and other related lung diseases. Employers need to give information about the impact of these risks and the serious potential consequences of exposure to young people in their employment.

The Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens recommends that young people do not handle animals infected with biological agents assigned to hazard group 4, ie those that cause severe human disease, pose a serious risk to employees, are likely to spread to the community and that have no effective prophylaxis or treatment available.

In turn, employers should inform young persons of their legal responsibilities towards the employer. This means following any safety arrangements implemented for their protection, including attending training sessions and complying with control measures, not acting in a manner that adversely affects their own health and safety and/or the health and safety of anyone else and to report any perceived or real shortcomings in protection levels to their employer.

In conclusion, a key component in managing the health and safety of young persons is the ongoing communication of safety messages and the guidance of mentors/supervisors to reinforce the true level of risk among young people and improving their perceptions of risk through training.

If you have any queries, please contact us.

8 March 2023 marks International Women’s Day. It’s a day that celebrates ‘the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women’ whilst also calling for equality – where men and women are treated the same. No one government, country, charity or group is responsible for it.

We hope you found this of interest. Here are some useful links

IWD: About International Women’s Day (internationalwomensday.com)

International Women’s Day 2024: UK Statement to the OSCE – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

International Women’s Day | World Vision UK

What is tinnitus?

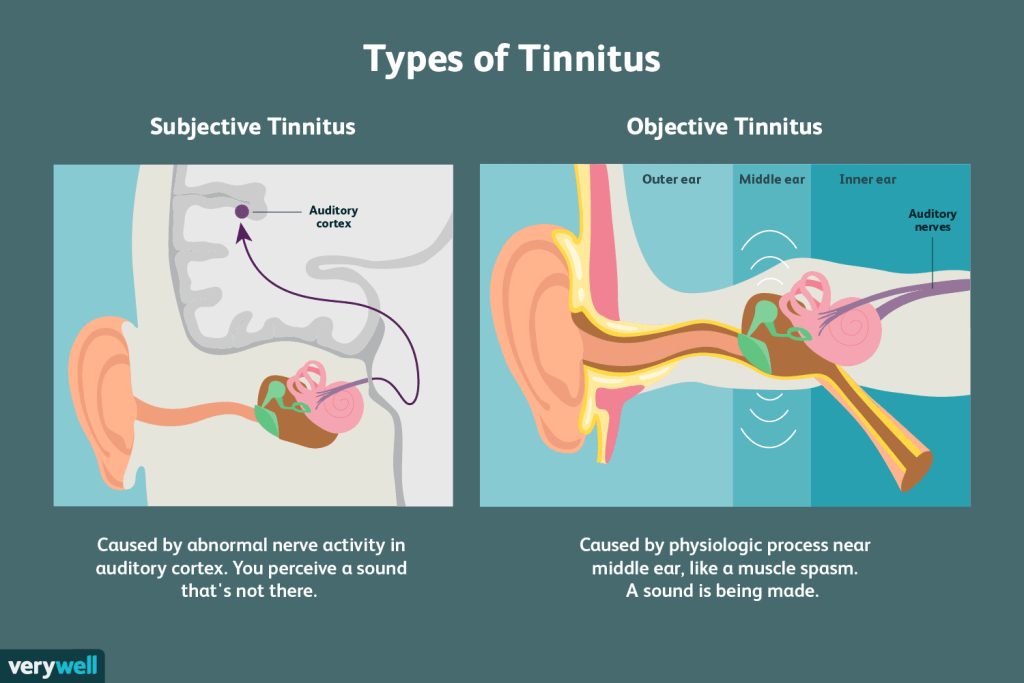

What is tinnitus?Tinnitus UK (formerly British Tinnitus Association) describes tinnitus as “the sensation of hearing a sound when there is no external source for that sound”. The symptoms may be felt as ringing, buzzing, hissing, clicking, whistling, whooshing sounds, etc and may be constant or intermittent, varying in volume from person to person. Tinnitus is thought to affect around 13% of adults in the UK.

According to Tinnitus UK, the noise may be in one or both ears, or it may feel like it is in the head. It may be low, medium or high pitched and can be heard as a single noise or as multiple components.

Occasionally people have tinnitus that can seem like a familiar tune or song, known as musical tinnitus or musical hallucination. Others have tinnitus which has a beat in time with their heartbeat — known as pulsatile tinnitus.

The symptoms are usually caused by an underlying condition with strong links to hearing loss in general.

The Tinnitus Awareness Week is an annual campaign dedicated to raising awareness and educating people about the causes, impact and management of tinnitus. This year’s event will be held from Monday 5 to Sunday 11 February.

Research conducted by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has indicated that the prevalence of tinnitus in workers exposed to noise at work is significantly greater than in workers not exposed to noise.

Therefore, jobs at particular risk of tinnitus are those characterised by loud or prolonged noise. For example, carpenters, construction and manufacturing workers, airport staff, musicians, call centre personnel and street workers could be among those at risk, as are people who work with chain saws, guns or other loud equipment as well as those who are exposed to loud music at work.

However, causes can also be completely unrelated to noise at work and linked to non-work-related hearing loss as well as ear infections or various illnesses such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, multiple sclerosis, anxiety, depression and Ménière’s disease.

According to the NHS, tinnitus can also be caused as a side effect of some chemotherapy medicines, antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin.

In the context of tinnitus, if noise in the workplace regularly reaches 80 to 85 decibels, to protect their staff, the employers could take steps such as:

The Control of Noise at Work Regulations 2005 apply to all industry sectors in Britain and aim to ensure that workers’ hearing is protected from excessive noise, which could cause them to lose their hearing and/or to suffer from tinnitus. See the Noise topic for information and guidance.

The HSE warns that many thousands of people are exposed to loud noise at work that may be a risk to their hearing.

In addition, ototoxic chemicals — substances which can harm hearing, even in the absence of noise levels — also carry risks which can be under-acknowledged, but are associated with often life-changing effects related to hearing loss. See our feature The life-changing risks of ototoxic chemicals.

In a survey, 42% of tinnitus sufferers believed that their condition had an adverse effect on their work, and loss of concentration, lack of sleep and anxiety associated with the condition can all make working more difficult. However, tinnitus can also impact on working in other ways including, for example, difficulties:

Employers also need to understand their responsibilities to staff with tinnitus or hearing loss under the Equality Act 2010 and will need to be prepared to make reasonable adjustments to support staff with hearing difficulties.

It is recommended by Fit for Work advisors that people who have hearing loss or tinnitus inform their managers of their condition and discuss changes that could help, such as moving to a different workstation, changing meeting venues or reducing stress.

Also helpful is an online resource called Take on Tinnitus. It has been designed primarily for people who have just begun to experience tinnitus. However, it is also a valuable resource for those who have experienced the condition longer term.

Some cases of tinnitus, such as those caused by the build-up of ear wax or because of an ear infection, can be treated by a doctor. In other cases, there is no cure, and treatment is focused on developing coping mechanisms in order to live with the condition. Various therapies may be helpful including the following.

A wide range of treatments and a number of specific medications, including antidepressants, amitriptyline and melatonin for example, have been reviewed by Tinnitus UK and evaluated using an extremely helpful traffic light system, based on their safety and efficacy.

Tinnitus UK runs a chat service via its website.

In addition, there is a network of tinnitus support groups around the country, listed via Tinnitus UK’s website, where people can develop and learn about new coping skills and gain inspiration and encouragement from others.

Tinnitus UK runs a large research grants programme to support tinnitus research. It recently partnered with scientists and academics from the Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre and the Universities of Nottingham and Newcastle to conduct innovative research, using imaging data from thousands of brain scans held in the UK Biobank, a major national and global health resource. It is thought that chronic tinnitus may be associated with changes in the structure of the brain, and that reversing these changes might prove effective in the treatment of the condition.

It is estimated that tinnitus affects over seven million people in the UK at present, and many people elsewhere around the world, potentially causing stress, sleep difficulty, anxiety and compromising hearing.

As research efforts continue, it is hoped that soon a cure for this enigmatic and distressing medical problem will be found.

If you have any queries, please contact us.

As part of an overall maintenance strategy, organisations should identify ageing fire precautions and have in place a regime to maintain such items.

As part of an overall maintenance strategy, organisations should identify ageing fire precautions and have in place a regime to maintain such items.

Many buildings will have fire precautions that can be described as physical assets that need to be properly maintained to ensure that they are fit for purpose and continue to function as efficiently and effectively as possible. This will ensure legal duties in relation to protecting relevant persons from the risk of fire are met.

All fire precautions will be subject to ageing, which if not managed appropriately can lead to equipment failure, which in turn can lead to future regulatory non-compliance, increased fire risks to life and greater business continuity issues in the event of a fire.

As part of an overall maintenance strategy, organisations should identify ageing fire precautions that may require a maintenance regime that goes beyond “best practice”, and put into place the regime to maintain such items.

Article 17 of the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 states that “where necessary in order to safeguard the safety of relevant persons the responsible person must ensure that the premises and any facilities, equipment and devices provided in respect of the premises under this Order … are subject to a suitable system of maintenance and are maintained in an efficient state, in efficient working order and in good repair”.

It should be noted that similar requirements are contained in the respective legislation for Scotland and Northern Ireland.

In this context, “where necessary” can be taken as meaning that the duty holder must do what is reasonable to protect relevant persons in terms of the maintenance needs of the facilities, equipment and devices provided under the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005.

In turn, these can be described as the general fire precautions that will include measures:

The key part of Article 17 is the requirement for these elements to be maintained in an efficient state, efficient working order and good repair. Guidance for enforcing authorities notes that this is a three-part test that can be best described as follows.

Maintenance of general fire precautions is an essential part of the overall fire risk management framework and can form part of any formal enforcement procedures.

Government publication, Guidance Note No 1: Enforcement, states that risk assessments should include references to maintenance. It continues by stating that enforcing authorities are “expected to use their professional judgement in evaluating the maintenance of any equipment and devices provided in accordance with the risk assessment to protect all relevant persons in and around the premises from the dangers of fire”.

To meet the above requirements, those responsible for fire safety will normally adopt a regime of planned preventative maintenance based upon best practice (such as detailed in relevant British Standards) in conjunction with a reactive repairs regime in the event of defects occurring/being identified between maintenance schedules.

However, during its lifecycle all fire precautions can degrade due to age-related mechanisms and it may be the case that maintenance frequency and regimes could be required that are beyond those recommended in the British Standards. It is therefore essential that as part of the overall maintenance regime, such ageing is identified, considered and appropriate measures are taken to manage the risks.

When referring to ageing fire precautions, it is important to note that this does not necessarily relate to the chronological ageing process, rather ageing is “the effect whereby a component suffers some form of material deterioration and damage with an increasing likelihood of failure over the lifetime of the asset”.

As an example, a property can have fire door assemblies of the same age and specification throughout the premises, yet one assembly could be subject to greater ageing due to its location, frequency of use and potential for damage to occur through use.

The management of ageing fire precautions therefore begins with an awareness that ageing is not about how old the equipment is, but what is known about its condition, and the factors that influence the onset, evolution and mitigation of its degradation. This suggests that for those with responsibility for maintaining ageing fire assets, there is a need to:

As well as the physical ageing process, other factors will need to be given consideration. This can include obsolescence and a lack of spare parts or the disappearance of the original equipment manufacturer, or non-conformance with current safety requirements, codes, standards and procedures.

Competency, availability and organisation of the employees/contractors responsible for asset management are also essential to ensuring that this understanding of current and predicted asset condition is used when making asset management decisions.

BS 9997: Fire Risk Management Systems notes that organisations should “plan, document, implement and manage the processes for maintenance and testing of fire safety systems to ensure that they operate correctly in the event of fire”.

As part of this, an organisation may require an “ageing maintenance programme”. This should detail the actions necessary to ensure any ageing fire precautions are maintained in an efficient and cost-effective way. The main elements of such a plan will be as follows.

It should be noted that within an ageing maintenance programme there may be differing schedules from those in relation to statutory compliance requirements being met through normal best practice. Where this is the case, the ageing maintenance programme needs to interface with such compliance requirements.

It should be noted that management of ageing fire precautions will require regular monitoring, review and revalidation following any unwanted incidents, major repairs, refurbishment or replacement of key items.

Managing ageing fire precautions effectively may require a shift in the way fire asset condition is regarded, assessed and maintained. This requires a proactive approach with a thorough understanding of the fire asset ageing mechanisms and condition, and the ways in which assets interact (including cause and effect).

The characteristics of an “ageing asset” can be defined as when:

If you require further information, please contact us.